Welcome to Weird, Wild, Wonderful Nevada

The Clown Motel in Tonopah, Nevada. | Photo by Louiie Victa; Illustration by Lille Allen/Eater A journey through Nevada’s eccentric side — where the ghosts are real, the art is immersive, and the weirdness has no bounds To many outsiders, Nevada is just the desert landmass that surrounds the glamorous, neon-drenched dreamscape of Las Vegas — a state whose name is mispronounced as often as it’s misunderstood (it’s Nev-add-uh). Others know Nevada to be ghost country, not just for its literal ghost towns, but for the apparitions rumored to haunt its century-old hotels and saloons. The state is, of course, the backdrop to Area 51 and (allegedly) classified extraterrestrial activity. It’s the collective memory of mushroom clouds blossoming over the Mojave Desert. It’s the rootin’-tootin’ Wild West. These images all coalesce into the tapestry of a state unified by the weird, wild, and wonderful. All of this to say, Nevada isn’t just drawn to the strange — it depends on it. Its history, infrastructure, and identity have been stitched together in secrecy and by speculation, which, in turn, have shaped the state’s appetite for the uncanny, the campy, and the downright surreal. I’ve lived in the Battle Born State since I was 14. Zak Bagans’s haunted museum sits just down the street from my house. The bar where my friends and I regularly celebrate birthdays glows with Atomic Age memorabilia. My weekend road trips include renegade art exhibits of upturned cars and spectral recreations of The Last Supper, often bookended by stops at alien-themed gas stations and beef jerky stands. Here, roadside restaurants and watering holes serve as waypoints and mythmakers, where strangers trade ghost stories over hotel bar counters, gather in a restaurant near Area 51 to compare unexplainable night sky sightings, and refuel with cherry-steeped beer from a remote brewery that alone can justify an hourslong drive. Janna Karel Cathedral Gorge State Park. My previous road trips throughout the state have featured stops at attractions that are pointedly bizarre — like artist Ugo Rondinone’s psychedelic Day-Glo monoliths that comprise Seven Magic Mountains. I’ve journeyed to many geologically surreal destinations: Take, for example, the soaring spires and person-wide slot canyons that rise from the pale siltstone and clay shale of Cathedral Gorge State Park. For the past decade, I have been telling my friends that next year is the year that I’ll join them on a silica-coated dry lake bed managed by the Bureau of Land Management for Burning Man, where some 70,000 people erect a city of tents, temples, and flame-spewing octopuses every August leading up to Labor Day. The West has long been a mirage — the draw of exploration, ambition, and self-invention shimmering like water: imminently ahead but just out of reach. Nevadans may be uniquely predisposed to look for things that are weird, says Michael Green, chair of UNLV’s history department. Consider the boom-and-bust mining towns of early Nevada and the resulting transience that lends itself to ghost stories. There’s Area 51 and the patchwork of lore regarding what secretly goes on beyond its gates, just 80 miles outside of Las Vegas. Even today, more than 80 percent of the state’s land is federally owned. “There is some degree of secrecy associated with federal land; there is also a degree of secrecy associated with the mob,” Green says. Between the 1940s and 1970s, the mob — more specifically, the American Mafia — exerted sweeping control over Las Vegas casinos: It built them, ran them, and controlled the flow of money both on and off the books. The mob’s goings-on were generally limited to verbal agreements and handshake deals, with documents minimally used and even written in code. “There are so many things that have been done behind the scenes, under the table, that we figured there has to be more to the story,” Green says. Nevada’s preoccupation with the weird isn’t just about secrets; it’s also about the inherent wistfulness of the American Southwest. There’s the nostalgia shaped by the open road, Route 66, and cowboy iconography — all shorthand within pop culture for individualism and escape. For longtime Nevadans, that nostalgia may be more textured, based on yearning for a slower pace or the do-it-yourself era of Las Vegas before corporate monoculture took over the Strip. More broadly, the West has long been a mirage — the draw of exploration, ambition, and self-invention shimmering like water: imminently ahead but just out of reach. George Rose Getty Images Seven Magic Mountains near Jean, Nevada. In April, I traveled 479 miles to see the weirdest and wildest lore-steeped sites in Nevada. Flying 80 miles an hour down the 95 — past sun-hardened rock faces and thorny desert scrub — I blearily had visions of making the same trip by foot and on horseback. In Tonopah, Nevada, I read an epitaph for a pair o

A journey through Nevada’s eccentric side — where the ghosts are real, the art is immersive, and the weirdness has no bounds

To many outsiders, Nevada is just the desert landmass that surrounds the glamorous, neon-drenched dreamscape of Las Vegas — a state whose name is mispronounced as often as it’s misunderstood (it’s Nev-add-uh). Others know Nevada to be ghost country, not just for its literal ghost towns, but for the apparitions rumored to haunt its century-old hotels and saloons. The state is, of course, the backdrop to Area 51 and (allegedly) classified extraterrestrial activity. It’s the collective memory of mushroom clouds blossoming over the Mojave Desert. It’s the rootin’-tootin’ Wild West. These images all coalesce into the tapestry of a state unified by the weird, wild, and wonderful.

All of this to say, Nevada isn’t just drawn to the strange — it depends on it. Its history, infrastructure, and identity have been stitched together in secrecy and by speculation, which, in turn, have shaped the state’s appetite for the uncanny, the campy, and the downright surreal. I’ve lived in the Battle Born State since I was 14. Zak Bagans’s haunted museum sits just down the street from my house. The bar where my friends and I regularly celebrate birthdays glows with Atomic Age memorabilia. My weekend road trips include renegade art exhibits of upturned cars and spectral recreations of The Last Supper, often bookended by stops at alien-themed gas stations and beef jerky stands. Here, roadside restaurants and watering holes serve as waypoints and mythmakers, where strangers trade ghost stories over hotel bar counters, gather in a restaurant near Area 51 to compare unexplainable night sky sightings, and refuel with cherry-steeped beer from a remote brewery that alone can justify an hourslong drive.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26001808/IMG_5348__1_.jpg) Janna Karel

Janna Karel

My previous road trips throughout the state have featured stops at attractions that are pointedly bizarre — like artist Ugo Rondinone’s psychedelic Day-Glo monoliths that comprise Seven Magic Mountains. I’ve journeyed to many geologically surreal destinations: Take, for example, the soaring spires and person-wide slot canyons that rise from the pale siltstone and clay shale of Cathedral Gorge State Park. For the past decade, I have been telling my friends that next year is the year that I’ll join them on a silica-coated dry lake bed managed by the Bureau of Land Management for Burning Man, where some 70,000 people erect a city of tents, temples, and flame-spewing octopuses every August leading up to Labor Day.

Nevadans may be uniquely predisposed to look for things that are weird, says Michael Green, chair of UNLV’s history department. Consider the boom-and-bust mining towns of early Nevada and the resulting transience that lends itself to ghost stories. There’s Area 51 and the patchwork of lore regarding what secretly goes on beyond its gates, just 80 miles outside of Las Vegas. Even today, more than 80 percent of the state’s land is federally owned. “There is some degree of secrecy associated with federal land; there is also a degree of secrecy associated with the mob,” Green says. Between the 1940s and 1970s, the mob — more specifically, the American Mafia — exerted sweeping control over Las Vegas casinos: It built them, ran them, and controlled the flow of money both on and off the books. The mob’s goings-on were generally limited to verbal agreements and handshake deals, with documents minimally used and even written in code. “There are so many things that have been done behind the scenes, under the table, that we figured there has to be more to the story,” Green says.

Nevada’s preoccupation with the weird isn’t just about secrets; it’s also about the inherent wistfulness of the American Southwest. There’s the nostalgia shaped by the open road, Route 66, and cowboy iconography — all shorthand within pop culture for individualism and escape. For longtime Nevadans, that nostalgia may be more textured, based on yearning for a slower pace or the do-it-yourself era of Las Vegas before corporate monoculture took over the Strip. More broadly, the West has long been a mirage — the draw of exploration, ambition, and self-invention shimmering like water: imminently ahead but just out of reach.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26003543/1410873410.jpg) George Rose Getty Images

George Rose Getty Images

In April, I traveled 479 miles to see the weirdest and wildest lore-steeped sites in Nevada. Flying 80 miles an hour down the 95 — past sun-hardened rock faces and thorny desert scrub — I blearily had visions of making the same trip by foot and on horseback. In Tonopah, Nevada, I read an epitaph for a pair of brothers buried in the cemetery next to the Clown Motel: two boys who grew up in Montenegro, traveled to the shores of the Adriatic Sea, then boarded a steamship to journey to the United States — only to be killed by a runaway mine cart 200 feet beneath the desert town. I stood in the shade of the Mission Revival-style railroad depot in Rhyolite, now a ghost town, where fortune-seekers arrived by train in 1907 with the promise of building a life in the state’s biggest mining camp — only to board that same train just one year later when the town began to decline. I traced my fingers over the bullet holes in the walls of Pioneer Saloon in Goodsprings, Nevada, and sensed the presence of the miner who lost his life over a poker game gone wrong.

This highway-honed wistfulness has become an integral part of Nevada’s folklore. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, when Nevada was in the thick of its mining boom, stories abounded of rich deposits gone lost. These narratives often took the form of an old prospector who emerged from the wilderness, unable to recall where he found the treasure, historian Ronald M. James writes in Monumental Lies: Early Nevada Folklore of the Wild West. Others involved “a dog running off, leading its owner on an untrodden path, or a donkey kicking a rock that reveals the gleam of gold.” This trope is behind the apocryphal story of Jim Butler, the prospector whose accidental discovery of the Mizpah Ledge silver vein led to Tonopah’s founding: One of his donkeys wandered off, and when he picked up a rock to throw at it, he was struck by the stone’s unusual weight.

If I wanted to better understand my state’s fascination with the weird, I reasoned that I should follow Butler’s path to what is now Tonopah, for a stay at the Mizpah Hotel.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26003127/MIZPAH_LADY_IN_RED_ROOM.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

I want to be clear: I don’t believe in ghosts. But that doesn’t mean the idea of them doesn’t scare me. So I passed on the opportunity to book the Mizpah Hotel’s Lady in Red Suite — a room that had been the private quarters of a sex worker, known in thinly veiled misogynistic lore as the “Lady in Red,” who was murdered by a jealous client more than a century ago and is rumored to wander the halls since. “Visitors report seeing her. Some staff have seen her. She really likes to frequent the fifth floor,” says Chavonn Smith, the front desk manager of the Mizpah. “She’s not an angry ghost. But she does not like women very much.” Instead, I booked a room where my bed was an old-timey wooden wagon.

Feigning bravery, I joined a ghost tour that began in the hotel’s turn-of-the-century lobby — marked by burgundy patterned carpet, frosted-glass chandeliers, and Victorian camelback settees that seem made for collapsing onto should any of the basement’s rumored inhabitants appear. Only when we reached the unfinished floor that once held the hotel’s safe did our guide tell us the story of three enterprising miners who tunneled beneath the hotel and emerged through the bottom of the vault. After securing the hotel’s riches, one of the miners turned on the others. The next morning, the hotel manager unlocked the safe to find the money gone — and two dead miners left in its place. Visitors still recount catching glimpses of the betrayed miners at the hotel bar, their heads translucent and capped with carbide lamp helmets.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000871/MIZPAH_BUILDING_EXTERIOR.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000872/MIZPAH_BAR___LOBBY_AREA_4.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

Sure, these tales are tall. But in Nevada, ghost stories are more than just marketing or tourism fodder. In Monumental Lies, James writes that from their earliest days, Nevadans have entertained the idea of ghosts. Long before mining towns spun tales of haunted saloons, Indigenous communities of the Great Basin — like the Paiute and Shoshone, and the Washoe near Lake Tahoe — shared stories of ghosts that warned of danger and spirits tied to sacred waters and ancestral places. As James notes, “much was appropriated but then confused, while other traditions were imagined and projected onto the cultures of the American Indians” — a tangle that shaped the state’s early folklore into a mix of belief, invention, and sometimes mockery of its earliest inhabitants.

What makes Nevada’s ghost stories feel different — weirder, even — than those of other allegedly haunted states is how deeply they’re rooted in its roads. In much the same way that cities like Tonopah, Goldfield, and Virginia City were built on the promise of silver, so too are they now buoyed by haunted tourism. “For many today, a pivotal way to approach the past is by contemplating its spiritual residue,” writes James. Stories like those of the betrayed miners — tales of greed, ambition, and unresolved endings — are part of how Nevadans make sense of a landscape shaped by boomtowns, busts, and disappearances. In a place where so much has been hidden or lost, locals and travelers continue to try to conjure spirits that may or may not have reason to linger.

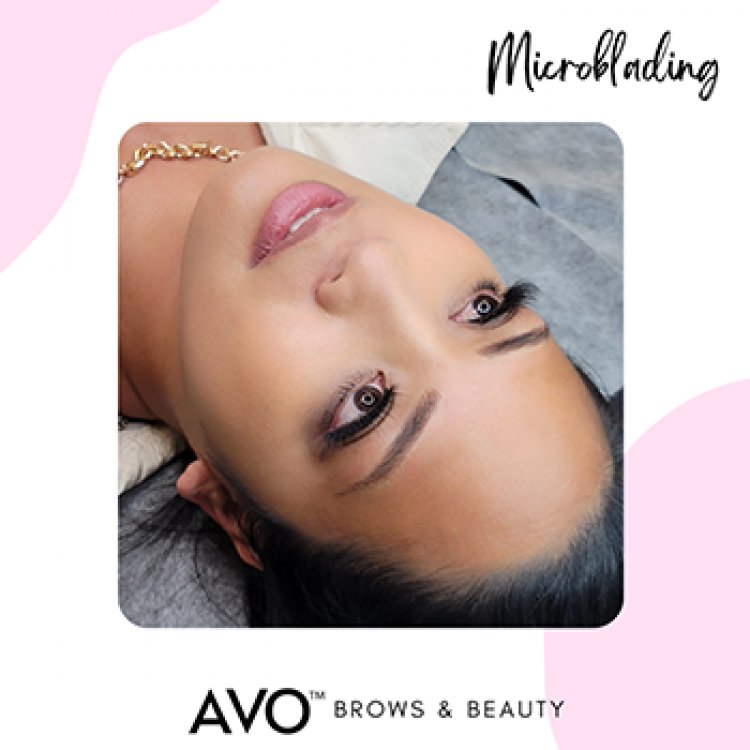

Tonopah has a population of about 2,000 people — 6,000 if you count the clowns. The 33-room Clown Motel opened in 1985 with a modest personal collection of 150 clown statues. When former art director Hame Anand took over as the motel’s CEO in 2019, he ran with the theme — adding thousands of clown murals, portraits, marionettes that probably come alive at night, masks that will almost certainly fuse to your face if you get too close, and one clown statue that I swear I saw wink at me. The whole thing is galling, baffling, deeply unsettling — and, naturally, a must-see tourist destination.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000875/CLOWN_MOTEL___MUSEUM___CLOWN_ROOM_2.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25997211/CLOWN_MOTEL___MUSEUM___CLOWN_ROOM.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000876/CLOWN_MOTEL_EXTERIORS_4.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000877/TONOPAH_CEMETERY.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

The motel’s property backs up to another supposedly haunted locale: the town’s old cemetery. Here, century-old headstones are updated by the Central Nevada Historical Society to include causes of death. Wandering through the copse of wooden crosses and metal tombstones tells the story of small-town Nevada in the early 1900s — where the Marojevech brothers failed to halt a runaway mine cart in the Belmont Mine, where local hero Big Bill Murphy was killed rescuing others in a fire in 1911, and where the “Tonopah plague” caused the deaths of 56 people in a four-month span in 1905. It’s a ledger of early Nevada, an undercurrent of reality beneath the honky-tonk myth of the Wild West.

Before hitting the road, I had lunch at Tonopah Brewing Co., where the walls are lined with awards for brewmaster Edward Nash’s tart fruited sours. But the food here is a sleeper hit, far better than one may expect from a brewery in Middle of Nowhere, Nevada. A French dip sandwich piles tender roast beef onto a pretzel roll slathered with horseradish and flanked by a glimmering side of jus. Molten fried cheese curds beg to be dunked into their accompanying ranch dressing. A Nashville-style hot fried chicken sandwich gets topped with a stack of cooling pickles and coleslaw. It all paired well with a flight of beers — the Cherry 51 witbier, brewed with cherries, and the Honey Wheat ale stood out as my favorites.

Driving back down to Las Vegas, I stopped in Goldfield (population: 231), with my sights set on the International Car Forest of the Last Church. Weird art in Nevada is hardly limited to the tech scion-curated display in Black Rock City. Dozens of junk cars, school buses, and ice cream trucks are half-buried like offerings, their hoods entombed in the hard earth, tail lights propped up like grave markers, chassis exposed like bodies after exhumation. These cars await wandering artists who will anoint them with spray paint. Is this a meditation on decay? A post-industrial necropolis? A bold indictment of consumerism’s terminal velocity? Or — and stay with me here — is it just extremely funny to bury a minivan in the desert and hand out cans of Krylon like communion wafers? Art is subjective.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000869/IMG_5985.jpg) Janna Karel

Janna Karel

Seeking more weird desert art, I ventured to Rhyolite (population: 0), a ghost town once so destined to be the largest mining operation in the state that a railroad was built in 1906 to connect it to Las Vegas. A Mission Revival depot soon followed, servicing the 50 freight cars that ran per day. But within months of its completion, more people were leaving Rhyolite than arriving, according to the Bureau of Land Management. Just downhill from the depot — and the crumbling remains of the bank and schoolhouse — lies the Goldwell Open Air Museum. Thirteen spectral figures, cloaked in gauzy white plaster, loom over the sand in a ghostly parody of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. Rooftops peek out of the ground as if they’re being swallowed by quicksand. A 25-foot woman made out of pink cinder blocks — with yellow brick accents to indicate both her blond locks and pubic hair — stares silently into the distance.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000882/IMG_6035__1_.jpg) Janna Karel

Janna Karel

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000870/IMG_6015__1_.jpg) Janna Karel

Janna Karel

Nevada’s desert is part excavation site, part sandbox: a squared-off plot where some come to unearth buried histories, while others come to play — shaping odd monuments before the wind levels them flat. Nowhere is that tension more vivid than in Rhyolite, where past ambition and present-day absurdity share the same forsaken earth.

Alongside its ghost stories and surrealist desert art, Nevada also deals its own brand of extraterrestrial weird. Driving south from Rhyolite into Las Vegas brought me to the Area 51 Alien Center in Amargosa Valley — a Brat-green gift shop/gas station/frozen yogurt cafe decorated in cardboard clip art aliens. It sells alien-face thongs; green-handed back scratchers; vials of soil allegedly sourced from Area 51; “Interstellar Sandwiches,” including a triple-decker club and drippy “Alien Burgers” with sauteed mushrooms; and, for $5, a turban-clad Alien Zoltar, who predicts that something lost will turn up very soon. This is the kitschy end of Nevada’s alien fixation — part roadside spectacle, part intergalactic fever dream — joined by the E.T. Fresh Jerky bungalow in Lincoln County, the Outpost 51 Alien Museum in Boulder City, and the Alien Fresh Jerky compound just over the border in Baker, California, where a full-size UFO hotel is under construction.

The next day, I drove up Route 375 — better known as the Extraterrestrial Highway. The official road marker bearing that name, perched atop two 12-foot-tall poles, had previously been stickered into illegibility. The highway winds past the legendary Black Mailbox, rumored to be a drop site for alien communications, and the arched, galvanized metal Alien Research Center fronted by a towering metal figure. (I’m pretty sure the latter is a gift shop, though it’s never been open when I’ve passed through.) Follow the road and eventually you’ll drive through the gates of Area 51. But about 25 miles before that, you’ll arrive at the Little A’Le’Inn in Rachel, Nevada (population: 48).

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25997208/IMG_5642.jpg) Janna Karel

Janna Karel

Little A’Le’Inn has become a haven for the alien-obsessed, but its namesake stems from a typo, not anything out of this universe. After buying the Rachel Bar and Grill in 1988, owner Connie West tells me that her parents intended to name the cafe the “Little Ale’Inn” — a nod to the ales they served. But a printer’s error on the sign — an errant apostrophe — turned it into a name that just happened to rhyme with “alien,” West says, around the same time Las Vegas reporter George Knapp was breaking Bob Lazar’s now-infamous claims about working on an extraterrestrial spacecraft near Area 51. For West, the name feels almost like fate.

Before Matty Roberts’ viral Facebook event, “Storm Area 51, They Can’t Stop All of Us,” thrust the Little A’Le’Inn into the national spotlight, the restaurant had already cultivated its own community — one made up of UFO chasers and roadtrippers, or, as West puts it, “people who want to travel, to see places, to get off the pavement and the beaten path.” Visitors come with photographs of their own UFO sightings in hand. They mail West Polaroids and handwritten testimonials, many of which are taped on the restaurant’s gallery walls. The photos make me think about the unwavering light I saw bobbing over Great Basin National Park last summer. If I had snapped a photo, would it have made West’s wall?

Beyond the displays of photos and Area 51 memorabilia is a smattering of mismatched tables and chairs, a bar where customers sign dollar bills to be suspended from the ceiling, and a gift shop filled with bumper stickers and shot glasses (“Believe,” one reads). Outside, the restaurant is bordered by alien statues. A light-up flying saucer was a parting gift from the Galaxy Quest home-video release party, which took place in Little A’Le’Inn’s parking lot. A tow truck suspends a satellite dish-sized metal UFO — plastered with stickers from travelers who’ve passed through — donated by a friend of West’s father, Joe Travis. West says that a visiting artist asked for permission to paint on a blank wall. The artist left a purple mural of dead-eyed aliens, some engaged with humans in an interspecies kiss, that glows under black light.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000884/IMG_6039.jpg) Janna Karel

Janna Karel

Over “Saucer Burgers” and buttery white bread grilled cheese sandwiches, customers who commute among the Southwest’s national parks — Zion to Yosemite is a common trail — pick up easy conversation at Little A’Le’Inn, comparing stories of unexplainable sightings in the night sky. West says it’s this sense of openness and shared experience that has allowed the restaurant to continue to thrive. “We have a unique place where you’re free to communicate with each other [without judgment],” she says. “I think that’s why we have been in business so long.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25997243/ATOMIC___MISS_ATOMIC_ART_INTERIOR.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

Over time, Little A’Le’Inn became a nexus for weird Nevada experiences. There’s a warmth in the conversations that happen here, knitted among friends and strangers — of strange bright lights in the sky, of encounters in the barren stretches of Nevada’s night, of government secrets they seek to uncover. “I personally believe that if you look up and you look out, it’s too vast,” West tells me. “There are strange things in the sky, things I can’t explain. Hopefully, there’s something else besides us.”

In the 1950s, patrons at Atomic Liquors in Downtown Las Vegas looked up and out, too. They would gather on the roof of the city’s first freestanding bar with cocktails in hand and watch nuclear test explosions bloom on the horizon, as if they were fireworks instead of fallout. Back then, atomic tourism was part of the spectacle — proof of progress and power. Today, that bar leans into its strange past, its walls lined with Atomic Age paraphernalia and standees of Miss Atomic Bomb in her mushroom cloud swimsuit. It’s kitschy, yes, but also quietly haunting — a reminder that Nevada’s fascination with the unknown has revolved around the existential as much as the extraterrestrial.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/26000885/ATOMIC___EXTERIORS_1.jpg) Louiie Victa

Louiie Victa

In Nevada, weird isn’t an outlier, it’s the vernacular. From atomic tourism to ghost hotels, alien sightings to art cars, and all the tall tales of the Wild West, the state doesn’t just tolerate the bizarre: It builds around it, sells tickets to it, leaves the lights on for it. Maybe all the UFOs were just weather balloons. Maybe the ghosts were just creaks in the night. And maybe that clown never winked at me. The stories here are strange, and the sights often stranger. But they help make sense of a place long defined by what slips through fingers — silver, water, time, truth.

“From the earliest days, the West was wilder, harder hitting, harder drinking, harder ... everything ... than elsewhere. We know this to be true because legends confirm it,” writes James. Call it mythmaking or marketing, but out here, weird works.